A New Era of Thought and Exploration

When historians and philosophers use the term “modern,” they are generally referring to the period beginning from the year 1500. It was around 1500, Europe underwent a transformation in how people related to knowledge, power, and discovery. The modern mindset, marked by curiosity, empirical evidence, and human confidence, emerged from revolutions in navigation, printing, art, science, and religion. Columbus’ voyages challenged old geographical assumptions. Gutenberg’s printing press fuelled literacy and communication. Artists like Michelangelo reimagined the human body not as something to be ashamed of, but something to be celebrated. The Reformation questioned religious authority, and scientific pioneers began dissecting nature rather than simply accepting ancient texts.

This was the dawn of intellectual independence and forward-thinking inquiry.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626): Rebuilding Knowledge from the Ground Up

Origin: England

Often called the father of modern science, Francis Bacon saw that centuries of reverence for tradition had left human knowledge stagnant. Born in London, Bacon proposed a bold alternative: learn from the world, not just books. He rejected reliance on authority or abstract speculation.

True science, Bacon argued, requires us to spend time “purely and constantly” among the facts of nature, resisting the temptation to leap to conclusions. In other words: look, observe, test, then theorise.

For Bacon, knowledge wasn’t about contemplation. Rather, it was about control and improvement. “Knowledge is power,” he declared, and it should be used to serve humanity. He warned of “idols of the mind”, deep-seated biases that cloud judgment, and argued that we need intellectual tools as much as physical ones.

Reflection: What assumptions are you clinging to that might deserve a second look?

René Descartes (1596–1650): The Power of Doubt

Origin: France

René Descartes marked a turning point in modern philosophy by asking a deceptively simple but deeply unsettling question: What do I really know? Living through a time of scientific breakthroughs and religious conflict, Descartes saw traditional beliefs about the soul, the cosmos, and human nature come under intense scrutiny. Discoveries in anatomy revealed no trace of a soul, leading some, like Hobbes, to describe humans as machines. Galileo’s telescopic observations disrupted the Church’s vision of a perfect, Earth-centred universe. These challenges made clear that inherited beliefs could no longer be trusted without question.

In response, Descartes developed a method he called radical doubt. He began by systematically doubting all his previous beliefs: the evidence of the senses, the certainty of waking life over dreams, and even the truths of mathematics, which he imagined could be manipulated by a powerful, deceptive force. Stripped of all certainty, Descartes found one foundation that could not be denied: the act of thinking itself. “I think, therefore I am” became the cornerstone of his philosophy.

From this single certainty, Descartes rebuilt his philosophical system, arguing for the existence of a benevolent God to ensure the reliability of reason. His ideas laid the groundwork for modern rationalism and the importance of individual self-awareness in the search for truth.

Prompt: What core beliefs have you accepted without question? If you doubted them, even briefly, what deeper truths might you uncover?

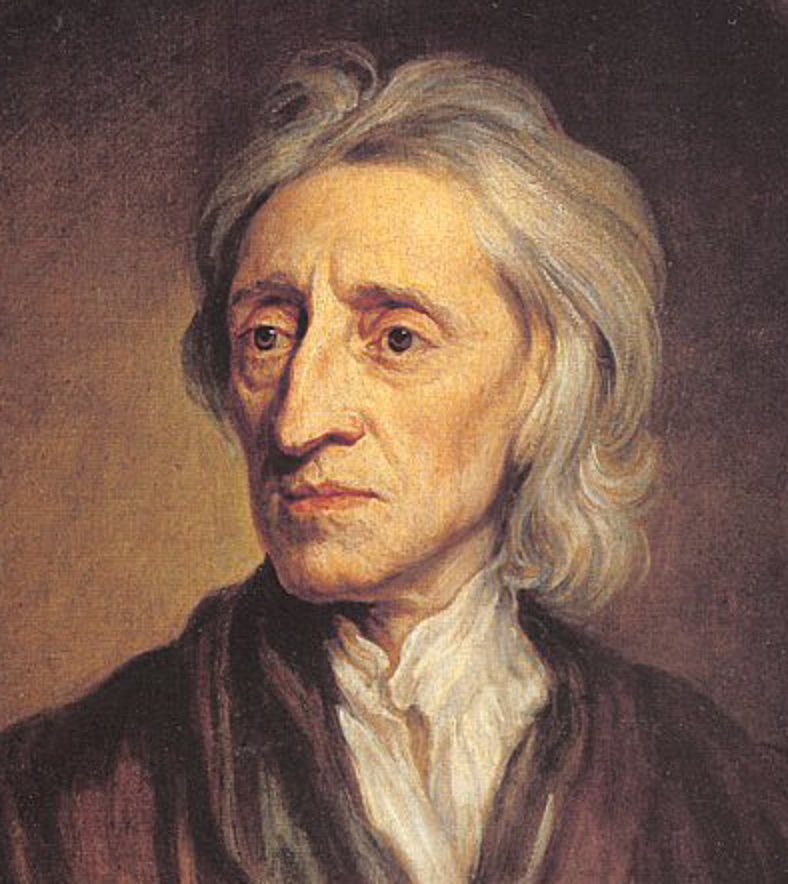

John Locke (1632–1704): Thinking for Yourself

Origin: England

Born in Somerset, Locke championed individual empiricism, the idea that knowledge begins with personal experience. He rejected the notion that we are born with innate ideas. Instead, our minds start as a “blank slate,” shaped by sensory experience and reflection.

Locke lived through England’s political turmoil, including exile during the reign of James II and return after the Glorious Revolution. These experiences fuelled his belief in tolerance, liberty, and the need to question authority.

His advocacy for religious freedom, outlined in A Letter Concerning Toleration, argued that government should protect civil rights, not enforce belief. Still, he imposed limits, distrusting atheists and religions loyal to foreign powers.

Reflection: Are your convictions grounded in your own reasoning, or inherited from others?

Voltaire (1694–1778), Montesquieu (1689–1755), and the French Enlightenment

Origin: France

In 1716, England witnessed the last execution for witchcraft. This marked the shift towards a more rational justice system. Previously, justice often relied on supernatural beliefs, such as trials by ordeal, where innocence depended on divine intervention. Philosophers began to reject these harsh methods, questioning how society could administer justice more rationally and humanely.

Montesquieu, a prominent thinker, famously remarked on the absurdity of punishing someone severely based on mere “conjectures” about their guilt. His skepticism highlighted the Enlightenment’s emphasis on evidence, reason, and the presumption of innocence, a radical shift from assuming guilt by default.

Voltaire, the leading French Enlightenment figure, drew significant inspiration from England, especially from thinkers like Locke and Newton. During exile in England, Voltaire witnessed a society more tolerant of religious differences, democratic in governance, and committed to freedom of thought.

In his Letters from England, Voltaire praised the English for their religious diversity and political freedoms. He highlighted Quakers as an example of simple, egalitarian, and peaceful religious practice, which contrasted sharply with hierarchical, authoritarian religion in France.

Actionable Takeaway: Embrace diversity of thought in your community. This is because innovation thrives where freedom and tolerance are strong.

The French Enlightenment blossomed in the 18th century with thinkers like Voltaire and Montesquieu, who questioned injustice and fought for freedom of thought. They saw superstition, tyranny, and inequality as barriers to human progress.

Voltaire and Montesquieu’s legacy was codified in the Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, which aimed to democratise knowledge and empower ordinary people.

Prompt: How can you help spread knowledge in your community?

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804): Reason and Responsibility

Origin: Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia)

Immanuel Kant, one of the most influential thinkers in modern philosophy, offered a rallying cry for the Enlightenment with a simple yet powerful phrase: “Sapere aude!” / “Dare to know!” For Kant, the Enlightenment was not merely about knowledge but about the courage to think independently and break free from intellectual dependence.

He defined Enlightenment as: “Man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity,” where immaturity meant the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from others. His message remains as vital today as it was in 1784: reason and autonomy are the pillars of true freedom.

What Is Enlightenment?

Kant’s essay, What Is Enlightenment?, defined the movement as the process by which individuals free themselves from the shackles of authority, superstition, and passivity. It wasn’t about attacking religion or politics outright, but about empowering individuals to:

- Think for themselves

- Question inherited beliefs

- Take responsibility for their understanding

He acknowledged that this transition wouldn’t be easy or quick. People often remain dependent out of fear or laziness, preferring someone else to think on their behalf, whether priests, kings, or teachers.

Freedom Through Reason

Kant advocated for a society where people could freely use reason in public discourse. He made a distinction:

- Private use of reason: When someone must obey within a role (e.g., a soldier following orders).

- Public use of reason: When individuals, as scholars or citizens, can debate and critique openly.

Kant urged rulers to allow this freedom of public reason. Progress, he believed, would naturally follow from the free exchange of ideas.

Reflection: In your workplace, home, or community, where might you be relying too much on others’ authority? Where could you think and speak more independently?

Reason as Moral Compass

For Kant, reason was not just a tool for scientific understanding, but a guide for moral action. He developed what he called the “Categorical Imperative,” which essentially asks:

Would it be good if everyone acted the way I am about to act?

This principle placed responsibility for ethical decision-making squarely on the individual. Morality wasn’t about external rules but about internal consistency and universal respect.

Actionable Takeaways:

- Use reason to examine your beliefs and actions..

- Take moral responsibility by asking if your actions are universalisable.

- Encourage open dialogue and debate as part of progress.

Legacy of Kant’s Enlightenment

Kant bridged the rational clarity of the Enlightenment with a deeper ethical and personal responsibility. He demanded the courage to earn freedom.

Reflection: Are you making moral decisions based on principles you’d apply universally?

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778): Freedom and the General Will

Origin: Geneva (modern-day Switzerland)

Rousseau’s Radical Thesis

Rousseau’s central argument in The Discourse on the Origin of Inequality is that civilisation corrupts. In contrast to Locke’s optimistic view of society as a protector of rights, Rousseau argued that humans in the “state of nature” were peaceful, equal, and free. It was only with the advent of private property that inequality and selfish competition emerged.

He famously wrote: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” For Rousseau, these chains were not just literal laws or institutions, but the moral degradation that came with modern civilisation.

The Social Contract and the General Will

In The Social Contract, Rousseau proposed a new political foundation. The key concept: the general will, the collective will of the people, aimed at the common good.

- True freedom, according to Rousseau, was not doing whatever one wants but aligning personal interests with the general will.

- The general will is not the same as the majority will. It is what is best for all, even if some disagree.

This idea justified collective decision-making and civic participation. In a well-functioning republic, citizens must be educated to transcend individual desires and pursue the common good.

The Role of Emotion and Morality

Unlike thinkers who prioritised cold rationality, Rousseau believed that morality and compassion arise not just from reason but from the heart, a sense of empathy and shared humanity.

He saw education not as filling minds with facts, but cultivating the natural goodness of children. His novel Émile argued for raising children with moral integrity and emotional awareness.

Legacy and Controversy

Rousseau’s ideas influenced both democratic and authoritarian traditions. The notion of subordinating individual will to a collective ideal can empower communities, but it also risks suppressing dissent.

- His thought inspired the French Revolution’s radical phase, particularly Robespierre’s pursuit of virtue through state power.

- Simultaneously, he laid groundwork for modern participatory democracy and civic responsibility.

Takeaways for Today

- Freedom requires responsibility: aligning self-interest with the common good.

- Morality is emotional as well as rational: compassion matters.

- Collective decision-making must balance unity with individual rights.

Reflection:

In what ways are we “in chains” today: socially, politically, or emotionally? What would it take to align personal freedom with the general good?

Prompt: What does real freedom mean to you, and how can it serve others as well?

Concluding thoughts…

Modern philosophy grew out of a deep desire to understand the world in new and better ways. It began when people started to realise that old traditions, beliefs, and authorities could not always be trusted. Thinkers like Francis Bacon, René Descartes, John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau each tried to answer important questions about truth, freedom, knowledge, and how we should live.

Francis Bacon believed that we must look carefully at the world, observe it with our own eyes, and build knowledge slowly through experience. René Descartes began with doubt and asked what we can know for sure. He showed that questioning is not a sign of weakness, but the beginning of clear thinking. John Locke reminded us that knowledge comes from what we see and feel, not just from books or tradition. He encouraged people to think for themselves and respect different opinions. Immanuel Kant said that real freedom means having the courage to think independently and live by our own principles. And Rousseau reminded us that reason alone is not enough. We must also care about others and work for the good of the whole community.

These thinkers had different views, but they shared something important. They believed that humans have the power, and the responsibility, to think for themselves. They challenged people to ask better questions, to avoid blind belief, and to combine logic with kindness. Their work helped shape the modern world, including science, education, politics, and ethics.

Today, their ideas are still relevant. We live in a time full of noise, opinions, and quick answers. But modern philosophy invites us to slow down and think carefully. It asks us to look again at what we believe, why we believe it, and how we treat others. To be modern is not just about using new technology or following trends. It means having the courage to learn, to grow, and to act with honesty and compassion.

In our own lives, we can follow their example. We can pause before making assumptions, question what we are told, and seek to understand rather than judge. Most importantly, we can choose to use our minds, not just to get ahead, but to make life better for ourselves and those around us.