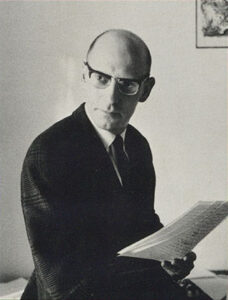

Michel Foucault, one of the most influential French philosophers of the twentieth century, never set out to write about schools in a direct or practical way. Yet his ideas about knowledge, power, and social control have profoundly shaped the way educators, researchers, and policymakers understand the modern education system. Foucault’s work helps us see that education is not only about what students learn, but also about how learning shapes who they become and how they view authority, truth, and themselves.

Schools as Systems of Power and Control

In his book Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault examined how institutions such as prisons, hospitals, and schools use subtle methods to regulate behaviour. He introduced the concept of disciplinary power, a form of control that works not through punishment, but through surveillance, routines, and self-regulation.

A classroom is a perfect example of this idea in action. Timetables structure every moment of the school day. Bells signal when one activity ends and another begins. Students sit in rows facing the teacher, learning to focus, stay silent, and wait for permission to speak. These seemingly ordinary practices train students to become disciplined individuals who internalise the norms of the institution.

For instance, the school timetable teaches students to divide their attention into fixed units of time. The report card quantifies effort and performance, transforming learning into measurable outcomes. Even the seating arrangement reflects hierarchies of power, positioning the teacher as the central authority. Foucault argued that these systems do more than organise learning; they shape identity and behaviour in subtle ways.

Observation and the “Panopticon” in Modern Education

One of Foucault’s most famous metaphors is the Panopticon, a circular prison design proposed by philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the eighteenth century. In the Panopticon, a single guard could observe all prisoners without being seen, leading prisoners to internalize surveillance and regulate their own behaviour.

In education, this idea translates into how students and teachers are constantly observed and evaluated. Surveillance takes many forms: CCTV cameras in hallways, classroom walkthroughs, standardized testing, and digital monitoring systems. Even digital learning platforms that track participation or time on task can be seen as modern extensions of Foucault’s ideas.

For example, a student who knows that their online activity is tracked tends to self-correct and stay “on task” without direct supervision. A teacher aware that lesson observations might influence performance reviews may modify their behaviour accordingly. These are modern manifestations of Foucault’s Panopticon, where individuals internalize the gaze of authority and self-regulate in response.

Knowledge, Curriculum, and the Construction of Truth

Foucault’s concept of the “regime of truth” challenges the idea that education is neutral. Every curriculum reflects choices about what knowledge is valued and what is excluded. When a national curriculum prioritizes Western literature, scientific rationalism, or certain historical narratives, it implicitly marginalizes other worldviews.

For instance, the dominance of standardized testing tends to privilege analytical, quantifiable knowledge while overlooking emotional intelligence, creativity, and ethical reasoning. Similarly, colonial histories in school curricula often present a one-sided narrative that reflects the values of those in power.

This is not necessarily intentional, but it reveals how education systems reproduce existing hierarchies of knowledge. Foucault invites educators to ask: Whose knowledge counts? Whose voices are missing? By doing so, teachers can begin to create classrooms that are more inclusive, diverse, and reflective of multiple perspectives.

Foucault in Practice: Contemporary Examples

Foucault’s influence is visible in many areas of modern educational research and reform.

-

Critical Pedagogy: Thinkers like Paulo Freire, who wrote Pedagogy of the Oppressed, built on Foucault’s insights to argue that education can either liberate or oppress. Freire’s approach to teaching as dialogue and reflection directly opposes the hierarchical, top-down model Foucault critiqued.

-

Restorative Practices: In schools that use restorative justice instead of traditional punishment, we see a shift away from the disciplinary mechanisms that Foucault described. Rather than controlling behaviour through fear or surveillance, these schools focus on accountability, empathy, and dialogue.

-

Data and Digital Learning: Foucault’s analysis of surveillance resonates with how educational technology now tracks attendance, engagement, and performance. Learning management systems collect data on every student interaction. While these tools can support learning, they can also reinforce the sense that students are constantly being watched and evaluated.

-

Inclusive Education: Foucault’s idea that norms define what is considered “normal” or “abnormal” is particularly relevant in special education. The concept of the “normal student” is socially constructed, not natural. Recognizing this helps educators challenge stereotypes and design environments that respect neurodiversity and individual difference.

The Role of the Educator

For teachers and school leaders, Foucault’s ideas encourage a deep kind of self-reflection. They remind us that every decision, from how we grade work to how we organize a classroom, carries implicit messages about authority, obedience, and knowledge. Educators can respond to Foucault’s challenge by:

-

Encouraging critical awareness: Invite students to question assumptions and explore how knowledge is produced.

-

Promoting student agency: Give learners more choice and voice in what and how they learn.

-

Balancing structure with freedom: Use routines to support learning, not to enforce conformity.

-

Reflecting on assessment: Consider whether grading practices reward compliance or genuine understanding.

Why Foucault Still Matters

In an age of constant measurement, ranking, and digital surveillance, Foucault’s insights are more relevant than ever. Schools today are shaped by data dashboards, performance metrics, and algorithmic systems that classify both students and teachers. His work warns us not to let technology and bureaucracy turn education into a mechanism of control.

At its best, education should empower individuals to think critically about the world they inhabit. Foucault helps us see that this goal requires more than good teaching methods. It requires awareness of the hidden systems that define what it means to succeed, to behave, and even to know.

Ultimately, Foucault’s legacy in education is a call to vigilance. By revealing how power operates through everyday routines, he challenges all of us: teachers, students, and policymakers. How can we make education a space for freedom rather than compliance?

Foucault and the Freedom to Think

Foucault’s ideas do not only belong in universities or policy discussions. They speak to anyone who has ever felt shaped by expectations, labels, or invisible rules. In this sense, his philosophy extends far beyond the classroom. It is about reclaiming the freedom to think for yourself.

Foucault believed that every society creates its own version of “truth.” From childhood, we are taught not only what to think, but how to think. The same is true in personal development. We are often told what success looks like, what happiness should feel like, and what a “normal” life entails. Over time, we may internalise these expectations so deeply that we mistake them for our own beliefs.

To apply Foucault’s thinking personally is to ask difficult but liberating questions:

-

What invisible systems shape the way I see myself?

-

Which values or goals have I accepted without questioning?

-

How does my daily routine discipline my thoughts and actions?

-

Where can I create space for genuine freedom?

Just as Foucault encouraged educators to question how schools shape minds, we can all reflect on how society shapes our sense of identity. When we do, we begin to see that true growth requires more than learning new information. It requires unlearning the invisible habits of thought that keep us compliant and predictable.

As Foucault once said, “Maybe the target nowadays is not to discover what we are, but to refuse what we are.” In education and in life, his challenge remains the same: to see the hidden structures that define us, and to choose, consciously, who we wish to become.