In my last post, Understanding Character Education, I explored what character education is and why it matters in schools. This post is more practical. I am sharing my notes from Character Toolkit for Teachers by Frederika Roberts and Elizabeth Wright (2018), which provides some examples of specific activities and routines for use with children and teachers to develop character. In my day-to-day work through pastoral leadership, the Good Citizens Club, and initiatives like peer mediation, I have learned that students do not just “pick up” good character by being in a decent environment. It is tempting to think character education works by osmosis, and I suspect many schools unconsciously treat it that way. But I have seen with my own eyes that character can be taught through specific lessons and activities, and that it can be woven into normal classroom life across many subjects, not just PSHE.

Character Toolkit for Teachers aligns with work from the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, which has shown that integrating character across the curriculum is both possible and effective, particularly in literacy where discussion, stories, and writing naturally invite reflection on motives, choices, and consequences. Another reason I have valued this book is that the authors make a point that teaching character and positive psychology is not only good for pupils. It can also support teachers’ own wellbeing.

Roberts and Wright provide practical activities to develop character strengths that enhance wellbeing and academic attainment, while also holding moral and civic value. In the notes that follow, I share several key ideas from the book, alongside activity ideas I have used myself, organised around four areas: gratitude, kindness, teamwork, and self-reflection.

Gratitude

Gratitude is both a feeling and a character strength. Research by Seligman and colleagues suggests that simple, regular gratitude practices can lift mood and reduce symptoms of depression (Seligman et al., 2005). In school, we have seen how powerful this can be when it is made concrete and child-friendly. One activity we organised with our marketing team invited children to share what they feel grateful for. It helped students notice the good in their lives and name it out loud. This is one of the videos we made through the Good Citizens Club:

A practical classroom routine recommended by Seligman et al. (2005, p. 416) is “three good things”. For seven days, pupils write down three good things that happened that day. To deepen the impact, you can add a few quick prompts: Why do you think this happened? What did you do that helped? How could you make it more likely to happen again? What did it mean to you?

A version I use regularly is even simpler. At the end of the day, I invite pupils to share one good thing they experienced or noticed. To keep it focused, I tell the class that only three people will share each day, and each person shares one thing. It takes only a couple of minutes, but it trains pupils to look for what is going well and to appreciate it.

Kindness

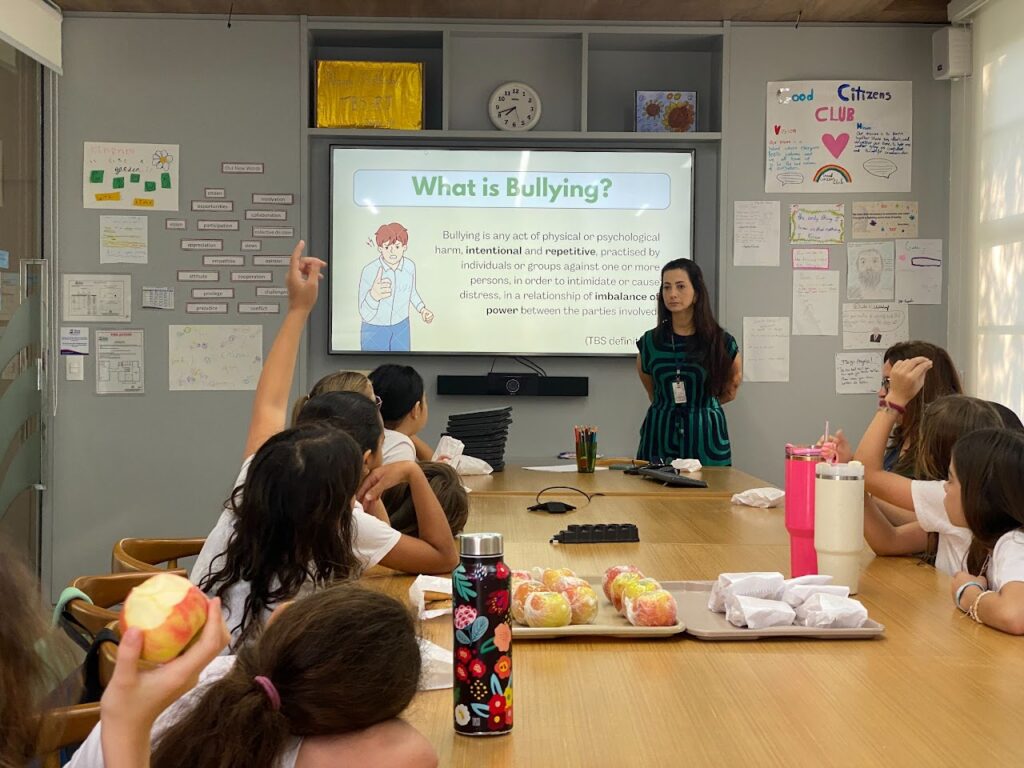

Kindness matters because it is the right thing to do, but it also has clear benefits for wellbeing and school culture. Studies suggest that acts of kindness can increase happiness (Lyubomirsky, Sheldon & Schkade, 2005). In schools, kindness also helps build a more positive social climate and can reduce the harmful effects of bullying by strengthening peer support and a sense of safety (Clark & Marinak, 2012).

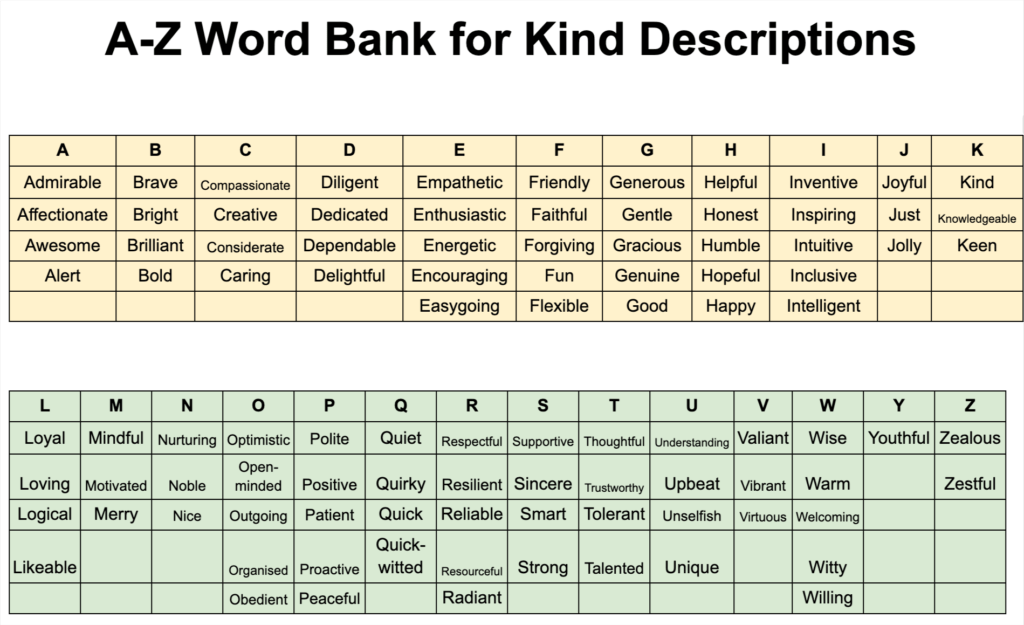

One of my favourite kindness activities is simple and highly effective. Each pupil writes their name vertically down the left side of an A4 sheet. If their first name is short, they can add their surname. The sheets are then passed around the class and classmates add a kind word or phrase for each letter, describing something positive about that person. For example, for “Alice”, one student might write “Amazing” for A, another “Loving” for L, another “Intelligent” for I, and so on. At the end, each sheet is returned to its owner. Students leave with a personal record of how others see their strengths, and the process itself trains the class to look for the good in one another.

I put together this Kindness Word Bank to help children come up with suitable words for their classmates:

Teamwork

Teamwork helps pupils feel they belong to their class and school. It is closely linked to collaboration, trust, helping others, and strong relationships, all of which support wellbeing and a positive school culture. When pupils learn to work well in teams, schools often see better learning, higher motivation, improved attendance, and stronger communication skills (Nariman & Chrispeels, 2016). Strong teamwork also supports wider school improvement by helping teams work more effectively and innovate (Somach & Drach-Zahavy, 2007).

One practical way to develop teamwork is through co-operative learning. This is structured group work where pupils learn with and from each other, rather than simply sitting together in a group (Smith, 1996). It works best when teamwork skills are taught deliberately. Pupils need chances to lead, make decisions, communicate clearly, and handle disagreements fairly.

In our Good Citizens Club, we build these skills through activities that matter to students’ daily lives. For example, they have worked together to create a child-friendly definition of bullying, agreed respectful expectations for the dining hall, and designed a simple rule system for sharing board games during break times.

A particularly popular activity is “Lava Leap Adventure.” In this challenge, students are told to imagine the floor has turned into lava and their team must cross the space without touching the ground. Each group gets a small number of “stepping stones”, such as paper plates or cardboard squares, and must plan a safe route. Students quickly realise that success depends on communication, problem-solving, coordination, and adapting their strategy when something goes wrong. It is simple and fun, but it gives pupils a real reason to practise teamwork, leadership, fairness, and calm conflict management in the moment.

School residential trips, which offer wide open spaces and more flexible time schedules, can also be a great opportunity for these sort of team building activities. The video below shows some highlights from one of our Year 5 school trips in Brazil:

Self-reflection

Self-reflection is a key part of building character. When students learn to reflect, they start to understand their values, notice what drives their choices, and practise living in line with what they believe. Over time, this supports better decision-making and more positive contributions to others (Lickona, Schaps & Lewis, 2002). In simple terms, self-reflection means looking back at what happened, why it happened, what you were thinking and feeling, and how your actions affected you and other people (Jubilee Centre, 2016). It is not an instant skill. It takes time to develop, but it supports almost every area of character and wellbeing (Harrison, Morris & Ryan, 2016).

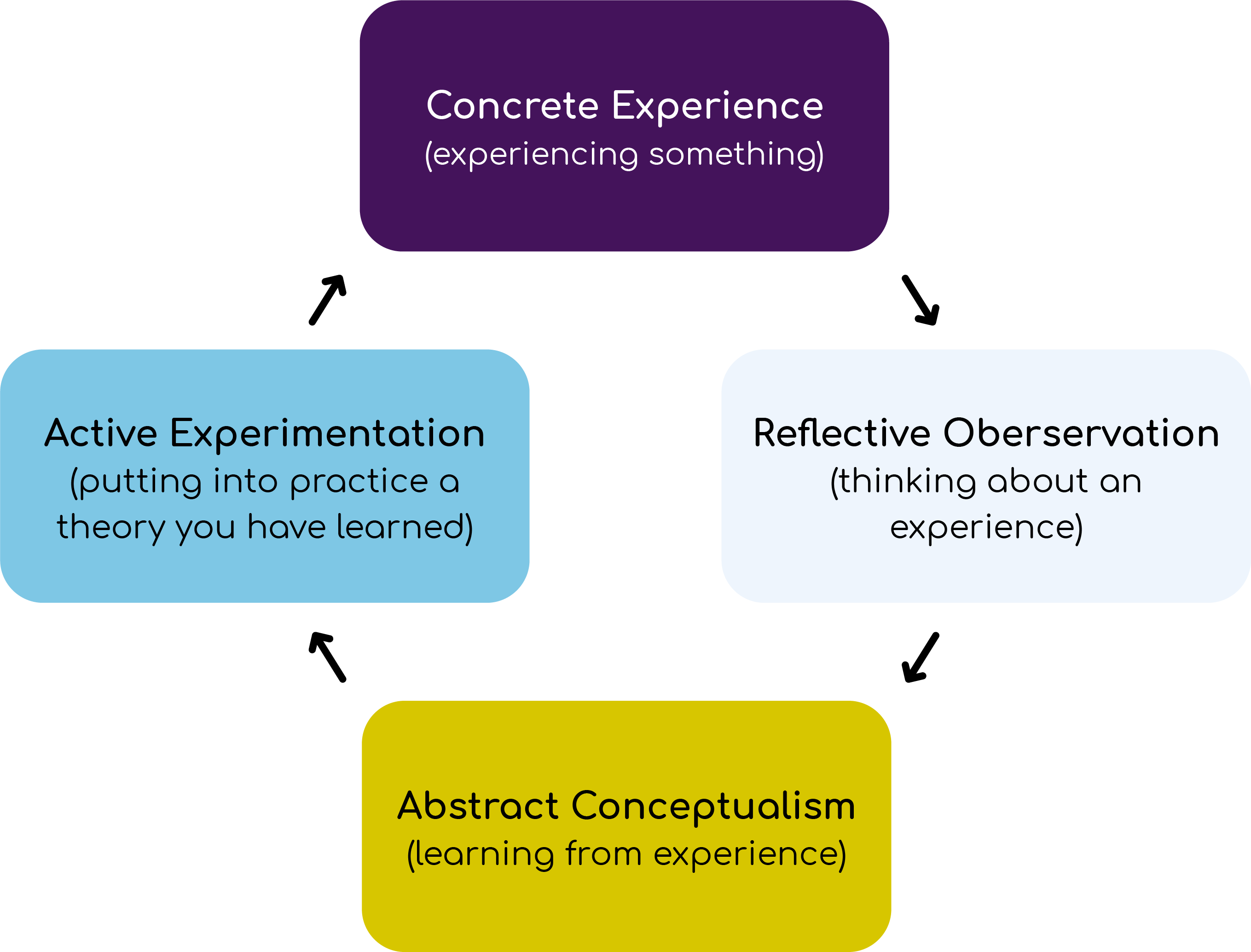

A useful way to understand its value is Kolb’s learning cycle. Students have an experience, think about it, form a new idea, and then try again in a new situation (Kolb, 1984). Each cycle builds self-awareness and strengthens judgement, not only in academic learning but in everyday life too (Roberts, 2008). The key is to make reflection a normal routine rather than a special event. For example, a short Friday reflection circle can invite pupils to share a small win, a challenge, and one strategy that helped. Reflection can also be linked to a weekly learner profile trait or virtue with one focused prompt, such as integrity: “When did I do the right thing even when it was hard?” Students can also set one specific goal at the start of the week and review it at the end using evidence of progress.

Self-reflection fits easily into existing classroom systems. In plenaries, students can self-assess against success criteria and explain what proves they met them. After feedback, they can identify a mistake pattern and name one change they will make next time. Schools can strengthen the home link by sending a simple weekly prompt for families, such as “What are you proud of this week, and what helped you?” Ownership grows when a “reflection leader” is rotated, with that pupil asking two closing questions at the end of a lesson or session. Consistency is easier when the whole school uses simple shared tools, such as the three questions “What? So what? Now what?” Younger pupils can use sentence starters like “I noticed… I felt… Next time I will…”, and quick traffic-light self-checks can help pupils choose one action step to improve.

Self-reflection is also especially valuable when supporting pupils who are struggling with behaviour. In those moments, I use six restorative questions to help the pupil slow down, make sense of what happened, and take responsibility in a constructive way. I discuss this approach in more detail in my last post, Understanding Character Education:

- What has happened?

- What were you thinking at the time?

- Who has been affected?

- How have they been affected?

- How did this make people feel?

- What should we do to put things right or make things better in the future?

Concluding thoughts…

The main lesson from Character Toolkit for Teachers is that character education works best when it is deliberate, practical, and woven into everyday school life. Students do not simply absorb good character by being in a good environment. They develop it through repeated experiences that teach them how to notice the good, act with kindness, work well with others, and reflect on their choices. The four areas I have shared here, gratitude, kindness, teamwork, and self-reflection, are not add-ons. They can be built into routines, lessons, and classroom culture across the curriculum, especially through discussion, stories, and writing. If there is one takeaway, it is this: small, consistent activities done well can shape who pupils become, and the process can strengthen staff wellbeing too.