Some years ago, I wrote a short blog post about the history of education. At the time, it felt like a satisfying overview, enough to sketch the big shifts and major thinkers who had shaped how we learn. But the more I have reflected, the more I have found myself interested in the underlying philosophy of education. What really is the purpose of education? What do we really believe about children, knowledge, authority, or the good life? And how do these beliefs, often invisible, shape the systems we build?

These questions pulled me even deeper, where I found myself questioning what it means to be human. That journey led me to study Professor David Hicks’ brilliant course, The Philosophy of Education, which brings together a wide-ranging and deeply reflective exploration of educational ideas from Plato to the present.

What follows is a distilled and structured version of the lecture notes I took during that course. I’ve written it as a synthesis of the most important themes and insights. My hope is that it serves as both a resource and an invitation, to think more deeply about what education is, and what it might still become.

Ancient Greek Education

What if you could design your own school with unlimited resources and full autonomy? Your first instinct might be to fill it with every conceivable subject: science, literature, geography, politics, religion, art, and more. But reality strikes: time is limited. Choices must be made, and priorities set. Do we favour science or creativity? Group learning or individual study? Physical or intellectual development? These questions quickly evolve from logistical planning to deep philosophical inquiry about what it means to live well.

Education as a Philosophical Project

Before deciding what or how to teach, we must ask: what is education for? One definition suggests: “Education is the process of learning and teaching the young the knowledge and skills necessary for successful adult life in the real world.” But what is the “real world”? Is it just the physical universe, or does it include moral, cultural, and even spiritual dimensions? Are we merely preparing children for jobs, or for lives of meaning, character, and self-fulfilment?

These questions shape curriculum design, teaching methods, and assessments. Should education prioritise student interests or societal needs? Is the teacher a guide or a master? With these queries, we step into philosophy.

The Greeks and the Birth of Educational Thought

We start by looking at the Ancient Greeks because they were among the first to treat education as a philosophical project. Around the 700s BCE, Greek culture began shifting. Instead of relying solely on oral storytelling, they began writing their most important myths and ideas. This seemingly technical change gave rise to deeper analysis of human knowledge.

Greek epics like The Odyssey are not just heroic tales. They examine the causes of war, the meaning of glory, and the tension between fate and free will. In contrast to other ancient cultures, which often portrayed humans as pawns of divine forces, Greek stories frequently placed humans at the centre of moral and intellectual struggle. Gods observed, debated, even admired humans. This humanistic perspective laid the groundwork for rational inquiry.

Philosophy Enters the Classroom

With figures like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, Greek education took on a more formal philosophical tone. Socrates championed the dialectical method, asking questions to uncover assumptions and sharpen understanding. This Socratic approach encourages students not just to absorb knowledge, but to actively examine it.

Plato imagined an ideal education system aimed at cultivating philosopher-kings. Aristotle, more grounded, saw education as the development of our rational and moral capacities. He believed all humans have a natural desire to know, and that education should nurture this through observation, conversation, and habit formation. Knowledge wasn’t just intellectual; it included emotional, social, and physical development.

Learning as Character Formation

Aristotle’s view of education included the systematic development of character. He identified key virtues needed to flourish in different life situations such as courage in the face of fear, temperance with pleasure, and wisdom in decision-making. These virtues weren’t innate; they were habits formed through guided practice.

This holistic vision treated the student not as a vessel to be filled, but as a complex being whose faculties could be cultivated over time. Education was not merely preparation for adulthood; it was life in progress.

Why It Still Matters

Modern education often oscillates between vocational training and test- driven outcomes. But the Greeks remind us that true education begins with a question: what kind of person are we trying to cultivate? If we aim for adaptable, thoughtful, and fulfilled individuals, then our schools must do more than deliver facts. They must provoke inquiry, develop judgment, and shape character.

Reflective Prompts:

- If education is preparation for the “real world,” how should we define that world?

- In your view, should teachers act more like guides, co-learners, or authorities? Why?

The legacy of Ancient Greek education is a model for how to think deeply about learning itself. And perhaps that’s the most enduring lesson of all.

Education as the Shaping of the Soul

In 431 BCE, Greece entered a period of devastating internal conflict with the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. This was a cultural and intellectual rupture. Two of the greatest thinkers of Western civilisation, Socrates and Plato, lived through this upheaval, and their philosophical inquiries reflect the moral and political chaos of their time.

Plato, deeply marked by the trial and execution of Socrates, turned to writing as a means of preserving and expanding their shared philosophical vision. His dialogues became vehicles for exploring truth, justice, knowledge, and the nature of the good life, all foundational questions for education.

The Myth of Gyges: A Dark Mirror of Human Nature

In The Republic, Plato recounts the myth of Gyges, a shepherd who discovers a ring that renders him invisible. With this power, Gyges lies, steals, rapes, and murders his way to the throne. The moral? If people knew they could get away with anything, most would succumb to their basest desires. For Plato, this story is more than simply a cautionary tale; it is a philosophical statement about human nature. Left unchecked, our desires make us dangerous.

If education is to shape character, it must assume that children are not naturally virtuous. They need guidance, structure, and sometimes compulsion to learn discipline and morality. This vision casts education as a form of ethical intervention, training the soul against its darker instincts.

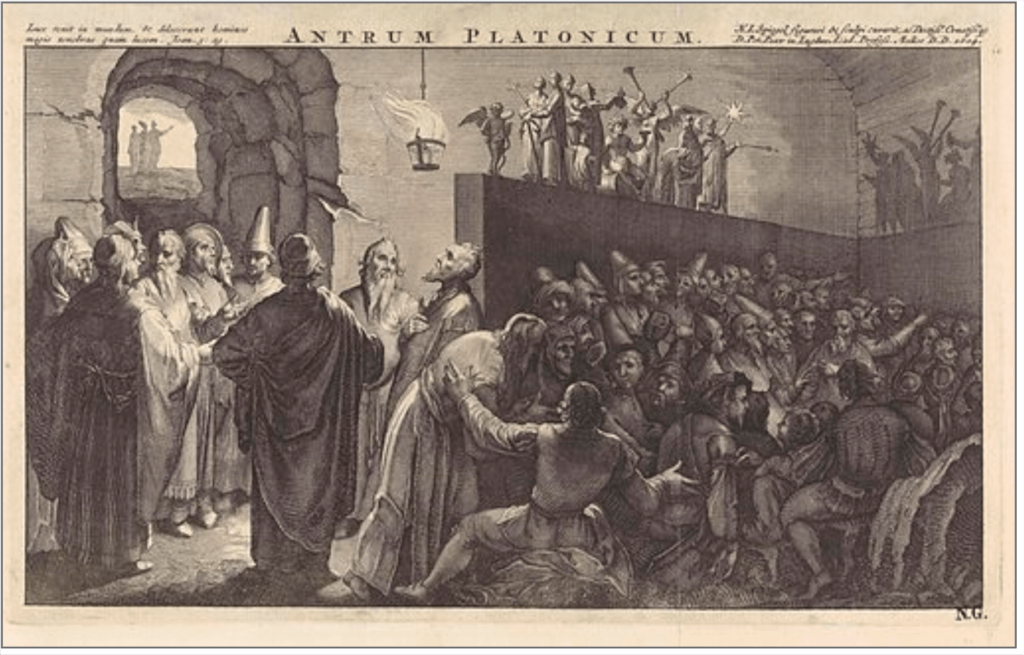

The Cave: From Ignorance to Enlightenment

In the same work, Plato offers the allegory of the cave, a metaphor for the human condition. Prisoners, chained in a dark cave since childhood, mistake shadows on the wall for reality. When one is forcibly freed and brought into the sunlight, the process is painful, but he eventually sees the true world. Enlightenment, for Plato, is not natural or easy; it is difficult, disorienting, and often resisted.

This allegory suggests that education is not about affirming student preferences or experiences. It is about challenging illusions and turning the soul toward truth. Crucially, it is the role of the enlightened, the teacher or philosopher, to return to the cave, out of pity and moral duty, to lead others to the light.

Plato’s Educational Vision: Order, Control, and Truth

Plato’s ideal education involves strict control over content. Art, poetry, and music are censored for their emotional influence and moral ambiguity. Homer and other poets are criticised for portraying gods as flawed, encouraging imitation of immoral behaviour. Education must protect children from such distortions and focus only on what is true and good.

In his late work The Laws, Plato even prescribes state-regulated games to ensure children play in ways that support moral and civic training. There is little room for creativity or spontaneous expression. Education, in this model, is not about personal exploration but about preparing individuals for their place in a well-ordered society.

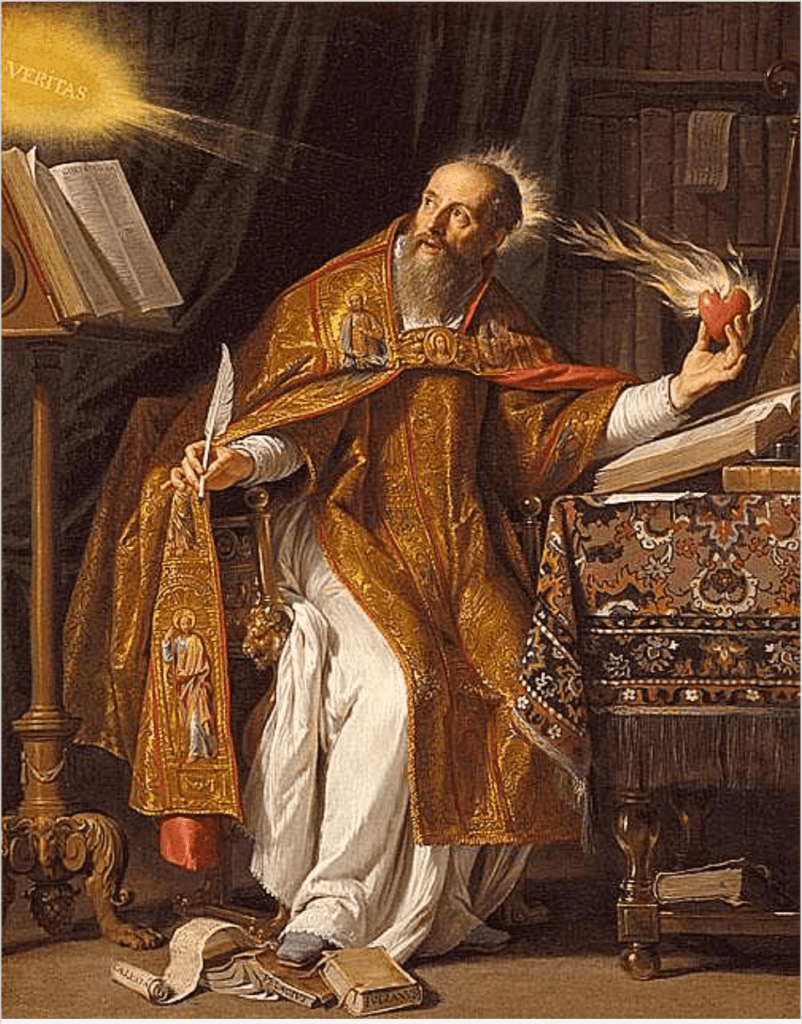

Augustine: The Inward Turn and Original Sin

Centuries later, as the Roman Empire declined and Christianity rose to dominance, Augustine built on Platonic ideas and gave them a Christian framework. In Confessions, he reflects on his life of sin, from childhood misbehaviour to lustful adolescence, and sees in himself a universal truth: human beings are fallen creatures.

Augustine embraces the doctrine of original sin. Even infants, he claims, are not innocent but possess the seeds of disobedience and selfishness. Education, therefore, is not simply the cultivation of reason but the correction of a corrupt nature. Learning begins with hardship, and moral transformation requires divine grace.

Christian Education: Authority, Discipline, and Salvation

For Augustine, the purpose of education is not intellectual enlightenment alone but salvation. This demands obedience, humility, and submission to divine authority. Pagan philosophy, especially that of Aristotle, is dismissed as misguided, while Plato is embraced for his spiritual orientation.

Augustine’s educational model is authoritarian. Truth is singular, revealed by God, and enforced by the Church and state. Teachers, like Christian rulers, have a duty to correct error, not just through persuasion but, when necessary, through force. From this perspective, physical punishment, censorship, and even torture are justified by the ultimate goal: the salvation of the soul.

Two Competing Visions of Human Nature

Underlying both Plato and Augustine is a stark view of human nature. Unlike Aristotle’s optimistic belief that humans naturally desire to know and flourish, Plato and Augustine see desire as dangerous and knowledge as something painful and rare. The child is not a curious explorer but a potential tyrant or sinner.

Their vision of education is hierarchical, compulsory, and morally charged. It is not about freedom or fulfilment, but about control, correction, and conversion. Whether through philosophy or theology, they argue, we must be made to become what we are not yet but ought to be.

Reflective Prompts:

- Do you believe people are naturally good, bad, or shaped entirely by their environment? How does this belief influence your view of education?

- Should education prioritise freedom and exploration, or discipline and moral training?

The legacy of Plato and Augustine is deeply embedded in Western educational traditions. Their influence remains visible in debates about curriculum, authority, and the moral purpose of schooling. Whether one agrees or not, they compel us to ask: what is education really for?

Renaissance Educational Visions

In 1085, the city of Toledo in Spain was reconquered by Christian forces after centuries under Muslim rule. But far from being just a political or religious victory, it marked a turning point in European intellectual history.

Toledo had been a major centre of learning under the Muslim Arabs, who had preserved, translated, and expanded upon the works of Greek and Roman thinkers. When Christian scholars arrived, they discovered a treasure trove of texts: philosophy, medicine, mathematics, which were mostly in Arabic. What followed was a quiet revolution: teams of scholars began translating these works into Latin, fuelling a dramatic expansion of Europe’s intellectual horizons. This was the birth of the Toledo School of Translators, a loosely organised but highly influential movement that reintroduced classical learning to a Europe that had largely turned its back on pagan knowledge.

This discovery raised a troubling question: how could such brilliance come from civilisations that lacked Christianity? Could it be that the Greeks and Romans had something valuable to teach, even without divine revelation?

Beauty as a Path to God

As Europe reawakened to ancient knowledge, tensions arose. Was it blasphemous to embrace beauty, art, and reason rooted in non-Christian traditions?

At Saint-Denis, near Paris, Abbot Suger pioneered the Gothic style of cathedral architecture, incorporating soaring arches and stained glass windows that depicted biblical stories. But not everyone approved. They feared that appealing to the senses, through art or music, risked corrupting the soul.

Suger’s defence? People couldn’t understand Latin sermons, but they could understand light and beauty. Art could elevate, not distract. This marked a subtle but significant shift: beauty, once suspect, was now seen as a potential bridge to the divine.

The Synthesis of Faith and Reason

The debate over ancient texts intensified in the 1200s when Thomas Aquinas sought to harmonise Christian doctrine with Aristotelian philosophy. He believed truth could be arrived at not just through faith but also through reason. This was a a bold stance in a tradition often wary of intellectual independence.

In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas laid out a method: present the argument, its counterarguments, and a reasoned response. His famous “Five Ways” aimed to rationally prove the existence of God, showing that faith and philosophy need not be at odds.

He also championed human agency. Rather than blind obedience, Aquinas argued that the highest form of life is self-governance. His vision pointed to a different kind of education, one grounded in reason, independence, and the belief that happiness in this life matters.

The Pushback Against Paganism

Not everyone embraced integration. Thinkers like Martin Luther violently rejected Aristotle and what they saw as pagan contamination of Christian teaching. In their view, philosophy belonged to the devil, and only faith and scripture should guide the soul.

This rejection sparked waves of censorship: books banned, art destroyed, and thinkers executed. Bonfires of the vanities, public burnings of jewellery, music, literature, were meant to purge the world of sensual and intellectual temptations. Self-education was dangerous; obedience was divine.

The Humanist Turn: Education as a Self-Directed Quest

Amid these clashes, a third path emerged during the Renaissance, one that celebrated the individual. Thinkers and artists like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Alberti re-centred education on the human experience.

Michelangelo’s David stands in poised resolve, representing human courage and agency. Similarly, Leonardo’s sketches of the human form weren’t religious: they were scientific, curious, full of wonder about the body and nature.

Leon Battista Alberti’s Self-Portrait of a Universal Man also captures this spirit. He writes not with confession or humility, but pride, listing his talents in law, music, painting, athletics, and science. Education, for Alberti, was joyful, wide-ranging, and self-directed. He saw books as beautifully alive and physical hardship as training for the soul.

This shift was profound: education was no longer about obedience or salvation alone. It was about becoming the fullest version of oneself, a life lived like a poem.

Foundations of a Liberal Education

Out of this new vision emerged the classical liberal arts curriculum: grammar, logic, and rhetoric (the trivium), followed by arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music (the quadrivium). But these were just the basics. Real education began when students took the lead in shaping their learning. The goal? Not docile believers, but free citizens.

Reflections for Today

The Renaissance opened new educational possibilities: a choice between obedience and exploration, doctrine and dialogue, authority and autonomy. Its legacy reminds us that genuine learning is not about force or conformity, but curiosity, courage, and self-discovery.

Reflective Prompts:

- In your own education, have you experienced moments where joy and curiosity drove your learning more than obligation? What sparked them?

- How can we, as learners and educators, balance the guidance of tradition with the freedom of self-directed exploration?

Through the Scientific Revolution

The year 1642 marked a symbolic transition in the history of ideas: Galileo Galilei died, and Isaac Newton was born. Both were monumental figures in science, but also philosophers who shaped how we understand the universe. Their lives bookend a transformative period in which the modern world began to emerge, intellectually, culturally, and socially.

This era followed a century of upheaval. By 1500, the world had expanded radically with Columbus’s voyages, leading to a new awareness of global diversity. Religion was in flux too, thanks to Martin Luther’s Reformation, which shattered the illusion of a single, unified Christendom. Europeans also became more aware of other world religions, leading to new questions about belief and tolerance.

Political and economic structures were being dismantled as well. Feudal hierarchies began to erode. The idea that one’s birth determined their fate gave way to new notions of personal freedom and mobility. Early voices began questioning the morality of slavery and inherited privilege. A spirit of innovation was taking hold in everything from agriculture to politics.

The Rise of Scientific Thinking

Amidst this ferment, modern science began to take shape. Astronomy, anatomy, medicine, and physics all saw rapid advances. Thinkers moved from relying on tradition and authority to trusting experimentation, observation, and reason.

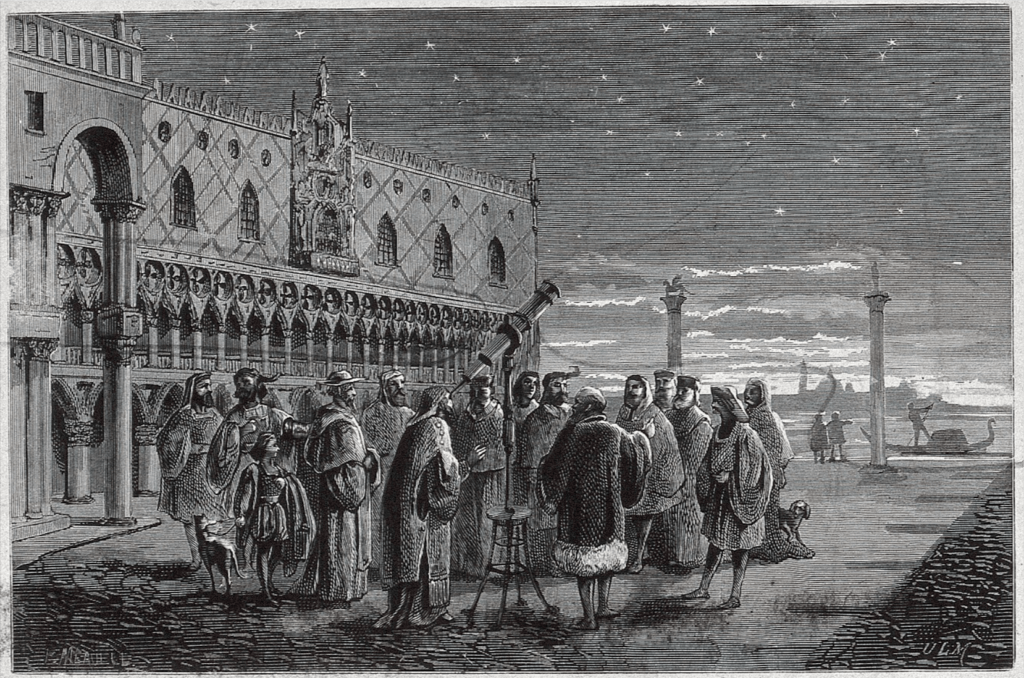

Galileo’s telescope revealed moons orbiting Jupiter, which was a direct challenge to the geocentric model of the universe. This upset long-standing theological frameworks that placed Earth at the centre of God’s creation. Science now offered not just new data, but a new method of understanding the world, one based on evidence, not inherited doctrine.

Francis Bacon championed this shift, arguing that knowledge should serve human flourishing. Rather than pursuing truth only for contemplation or spiritual transcendence, Bacon insisted that science should improve life on Earth. Knowledge became a tool for empowerment, not an escape from the world.

Galileo and the Two Books of God

Galileo famously argued that God authored two books: Scripture and Nature. Both reveal divine truth, but in different languages. Scripture teaches spiritual truths through metaphor, accessible to all. Nature, however, is written in the language of mathematics and requires observation and logic to interpret.

This view didn’t deny religion but redefined its scope. The Bible was not a science textbook, and conflicts between scripture and science were usually due to faulty interpretations. A truly devout person, Galileo argued, would use their God-given reason to study the natural world.

This stance was revolutionary. It called for tolerance, dialogue, and a dynamic interplay between faith and reason. It paved the way for science to flourish without necessarily displacing religion.

Education for the Modern World

These intellectual shifts demanded a new kind of education. Michel de Montaigne insisted that students should learn to reason for themselves rather than blindly follow authorities, even those as revered as Plato. Francis Bacon envisioned education that equipped individuals to shape and improve the world.

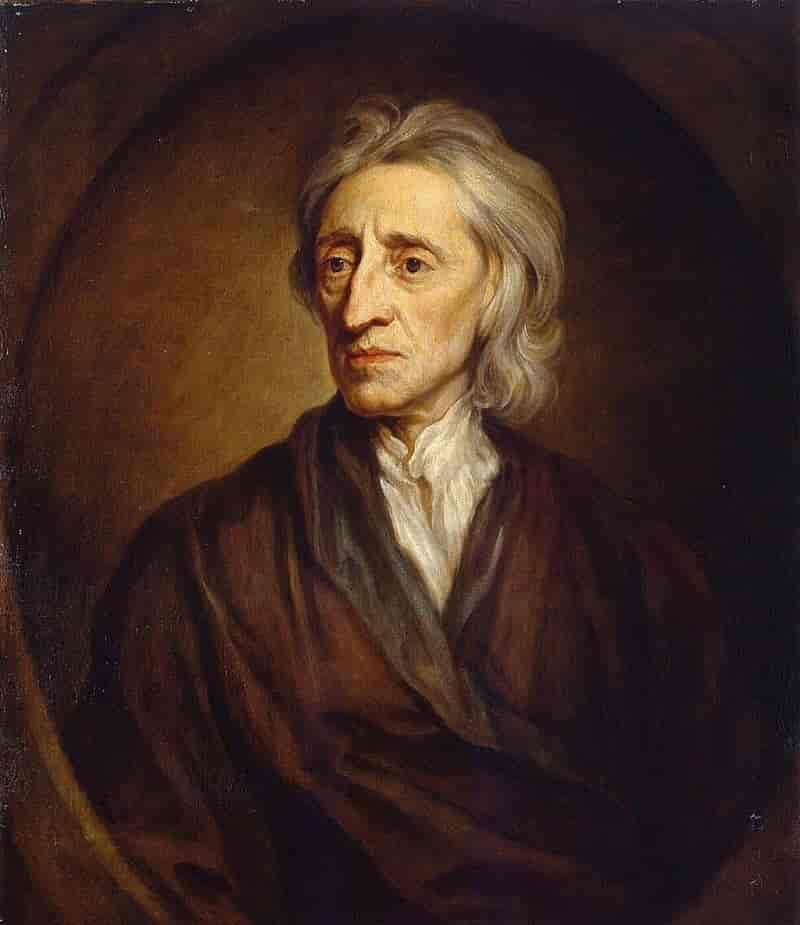

John Locke took these ideas further. In his view, education should cultivate both the mind and body. He argued against harsh discipline and advocated for learning through play, curiosity, and freedom. Children were not born sinful or fixed in nature; they were blank slates shaped by experience. Teaching should be customised, not standardised.

Locke believed that education must prepare people for liberty and self-governance. That meant encouraging independence, critical thinking, and moral responsibility. Even dancing, he said, was a valuable part of education, teaching grace, confidence, and social skill.

The Legacy of the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution reshaped not only what we know but how we come to know it. It created space for free inquiry, challenged authoritarianism, and elevated the individual as a rational, moral agent.

This transformation laid the groundwork for democratic ideals, modern education, and ongoing scientific progress. It replaced censorship with intellectual freedom and replaced obedience with exploration.

Reflective Prompts:

- How might education today better reflect the balance of freedom and responsibility that thinkers like Locke envisioned?

- Are there areas of life where science and tradition still struggle to coexist, and what can we learn from Galileo’s approach to such tensions?

Romantic Educational Visions

By the late 1700s, the Enlightenment had transformed the Western world. Rationalism guided religion, economics, and politics. Newton’s physics shaped scientific understanding, and Locke’s empiricism laid the foundations for liberal thought. New institutions of learning, free-market economics, democratic revolutions, and movements for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery were reshaping societies.

Amidst this apparent progress, Jean-Jacques Rousseau emerged as a critic of modernity. When he died in 1778, he had already set in motion a powerful countercurrent to Enlightenment rationalism, a return to feeling, instinct and the natural world. His ideas seeded what would become Romanticism, a movement that questioned whether reason alone could guide humanity toward fulfilment.

Rousseau’s Rebellion: The Tyranny of Reason

Rousseau argued that reason, when exalted above all else, dehumanised us. Industrialisation, he claimed, made us physically weaker and more dependent. Luxury dulled our instincts. Urban living detached us from nature. Rational education favoured conformity and obedience, not individuality or moral strength.

In his Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts (1750), Rousseau argued that progress in learning had not improved humanity but corrupted it. The Enlightenment had widened inequality, fostered vanity, and eroded genuine human connection. Modern society, he believed, encouraged us to perform rather than be, prioritising appearances, status and opinion over authenticity.

Emile and the Education of the Heart

Rousseau’s educational vision is embodied in his work Emile (1762), a fictional account of a boy raised outside the corrupting influences of society. Emile learns not through rote instruction but through direct experience, guided by a tutor who respects his individuality.

Rather than teaching abstract moral rules or theological doctrines, the tutor fosters Emile’s innate goodness and curiosity. Nature is the classroom. Life itself becomes the curriculum. The goal of education is not mere knowledge but the cultivation of autonomy, integrity and heartfelt connection.

One of the central characters Emile encounters is the Savoyard vicar, whose religious belief is grounded not in institutional dogma or rational argument, but in heartfelt conviction. Rousseau thus subverts the Enlightenment prioritisation of logic by suggesting that truth may be felt before it is reasoned.

Romanticism: Feeling Over Fact

Romanticism, influenced by Rousseau, rejected cold rationalism. It exalted emotion, imagination, passion and nature. It valued the mysterious, the sublime and the unquantifiable aspects of life. Friedrich Schleiermacher described religion as the “feeling of absolute dependence,” while Kierkegaard called for a “leap into the absurd,” privileging faith over logic.

The Romantics saw the Enlightenment as spiritually hollow. Where the Enlightenment sought control, Romanticism sought awe. Where science dissected, art dreamed. Where reason calculated, passion burned.

In education, this meant a move away from rigid schooling toward more holistic, child-centred approaches. Literature, art and direct experience with nature became the core of Romantic pedagogy. Formal institutions were often seen as stifling. True education, the Romantics argued, should awaken the soul.

The Power of Art and the Imagination

Romantic artists and writers gave form to these ideals. Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings captured the majesty and terror of nature. Poets like Wordsworth and Keats lamented that modern life had alienated us from the natural world and from ourselves.

Wordsworth’s exhortation, “Let nature be your teacher,” challenged the authority of bookish knowledge. In his poem The Tables Turned, he urged students to “quit your books” and find wisdom in the woods. For Romantics, nature was not just a backdrop but a moral and spiritual guide.

John Keats mourned the loss of wonder brought about by scientific analysis, writing that philosophy had “unweaved the rainbow”. The magic of existence, he suggested, had been stripped away by dissection and categorisation.

Romanticism in Practice: Alternative Education

Romantic educational thinkers sought to honour individuality, spontaneity, and emotional depth. This led to early movements for de-schooling and experiential learning. The arts and humanities were prioritised, not for their utility, but for their capacity to nourish the human spirit.

Instead of classrooms, nature and life itself became learning environments. The ideal was not the obedient, rational student, but the passionate, expressive and morally grounded individual. Authenticity mattered more than achievement.

Even among Romantics, however, views diverged. Some saw Romanticism as a total rejection of Enlightenment values. Others viewed it as a complement, a humanising balance to reason. Writers like Victor Hugo and Alexander Dumas fused Romantic adventure with Enlightenment ideals of justice, self-determination and reason.

Legacy and Reflection

Romanticism profoundly reshaped education by challenging the dominance of reason and advocating for emotion, imagination and individuality. It invited educators to see students as whole beings, not just minds to be filled, but souls to be stirred.

Reflective Prompts:

- In what ways does today’s education system balance the cultivation of reason with the nurturing of emotion and imagination?

- How might the Romantic emphasis on nature and direct experience be integrated into modern learning without abandoning rigour?

Strict German Reform

In 1806, Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Jena was not just a military defeat for Prussia but a profound blow to the German intellectual and cultural psyche. Jena, at the time, was one of the intellectual capitals of the Western world. Its universities hosted luminaries such as Hegel, Fichte, Schiller and the Humboldt brothers. The humiliation of defeat stirred a sense that Germany had not only lost a battle but a philosophical and moral footing.

Fichte, a central figure in this moment, saw the catastrophe not merely in military terms but as a failure of national character and philosophical vision. If Germany was to recover, it needed a radical educational reform grounded in the right moral and intellectual principles. His target: the Enlightenment emphasis on individual liberty, self-interest and limited government, which he believed had corroded German strength.

Kant, Obedience and Moral Education

Fichte drew deeply from Immanuel Kant, whom he saw as the philosopher who had finally “got it right” after centuries of failed philosophical inquiry. Kant’s emphasis on duty, moral law and the formation of character became central to Fichte’s vision for national renewal. Education, for both, was about moral training, not personal development or intellectual play.

Kantian education demanded obedience above all else. Children were to be taught to act not from inclination or desire, but from duty. As Kant wrote, “Above all things, obedience is an essential feature in the character of a child.” The aim was not to cultivate independence or creativity but to shape individuals into moral beings who would act out of a sense of universal obligation, detached from self-love or material interest.

Fichte’s National Education

In his 1808 Addresses to the German Nation, Fichte called for nothing less than a complete overhaul of German education. He proposed a system that would remake the German people into a unified moral and national body. This meant breaking with the past, rejecting Enlightenment liberalism and individualism, and constructing an education system that shaped a collective will.

Children, he argued, should be removed from their families and reared in state-controlled institutions. There, they would be immersed from birth in the values of duty, obedience and national unity. Personal inclinations and free will were not to be trusted. As Fichte put it, “The new education must… completely destroy the freedom of will in the soil which it undertakes to cultivate.”

This vision of national education was not designed to support diversity, creativity or exploration. Instead, it was a highly disciplined, centralised and uniform system intended to produce citizens who would serve the state and sacrifice individuality for the common good. The goal was to shape people who could no longer even imagine disobedience.

Religion and National Destiny

Religion played a key role in this moral education, though not in traditional theological terms. Fichte, like Kant, retained a belief in the spiritual realm, but framed it in moral and national terms. Students were not just members of a community for their lifetime, but links in an eternal spiritual chain connecting past, present and future Germans.

This metaphysical nationalism saw the German nation as a living organism, corrupted by foreign influences—particularly Enlightenment ideas from France and Britain—and in need of purification. The goal of education was to restore German “earnestness of soul” through strict moral training and cultural unity.

Legacy and Global Influence

Fichte’s ideas, implemented through the Prussian education system, became one of the most influential educational models of the 19th century. The founding of the University of Berlin in 1810, with Fichte as its first president, marked the institutionalisation of these principles. The system was admired and emulated, particularly in Eastern Europe and Russia, for its discipline and rigour.

Yet the long-term effects were double-edged. While Prussian education produced a literate, disciplined and efficient citizenry, it also laid foundations for more authoritarian political cultures. In contrast to Locke’s liberal individualism or Rousseau’s Romantic spontaneity, the Prussian model offered a blueprint for collectivist and state-driven education.

Reflective Prompts:

- How should modern education balance personal freedom with the cultivation of moral and civic responsibility?

- What risks emerge when education becomes a tool for enforcing national or ideological conformity?

Pragmatism and Progressivism

By 1913, with the election of Woodrow Wilson as President of the United States, progressivism had fully entered the American political mainstream. It was more than a political stance; it was a cultural and educational movement aimed at rethinking the individualistic values of earlier American life. Progressivism, with its emphasis on social reform, collective responsibility and the power of the state, sought to replace laissez-faire ideals with a new vision of shared progress.

Though the movement had many strands, its shared critique was clear: American traditions of limited government and self-reliance were inadequate for addressing modern industrial society’s challenges. The government, as Wilson wrote, should become “an agency for social reform,” replacing private charity with collective, legally mandated care.

Pragmatism: America’s Homegrown Philosophy

Philosophically, progressivism found support in pragmatism, a distinctly American tradition founded by thinkers like William James and John Dewey. At its core, pragmatism valued outcomes over abstract principles. The question was not “Is it true?” but “Does it work?” Ideas were judged by their practical consequences, not their logical purity.

William James emphasised the “cash value” of ideas: their tangible, real-world effects. He believed teachers needed to be well-versed in psychology, as education should be rooted in scientific understanding of the mind, not spiritual assumptions. Education, for pragmatists, was a means of shaping behaviour in real time.

John Dewey extended this into a full educational philosophy. Deeply influenced by Darwinian evolution, he viewed the world as ever-changing and conflict-driven. In Democracy and Education (1916), Dewey argued that truth is not eternal but socially constructed. Schools, therefore, should not transmit fixed truths but help students adapt and grow within a dynamic society.

Education as Social Continuity

Dewey redefined the goal of education: it was not about personal development but about initiating children into the shared experiences of the group. Individuals were “carriers of the life experience of the group,” and education was the means by which societies reproduced themselves. The focus shifted from cultivating the individual to sustaining the collective.

This meant classroom environments should mirror democratic communities. Students learned not in isolation but in groups, through shared projects and collective goals. Teachers were not authoritative figures but facilitators within the learning community.

Reformers and Activists

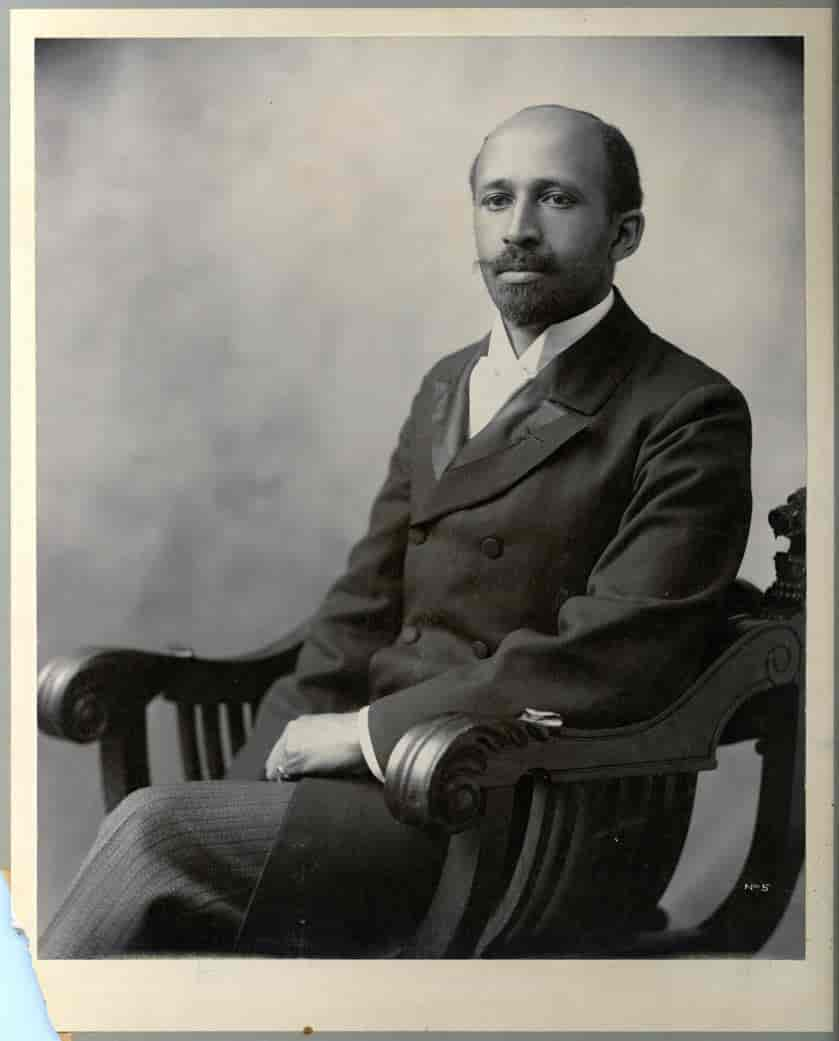

Progressive educators and reformers like Jane Addams and W.E.B. Du Bois carried these ideas into specific social causes. Addams, through her work at Hull House, focused on helping immigrants assimilate into American life. She rejected the idea that newcomers should simply be left to fend for themselves. Instead, she argued for a supportive, nurturing approach, what she called a “higher morality” of social obligation.

Du Bois, in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), described the painful “two-ness” experienced by Black Americans: torn between being American and being Negro. For him, education was a vehicle for both empowerment and transformation. He believed knowledge would lead to dissatisfaction and revolution, and he openly criticised religion as a barrier to racial and social progress. Education, in this view, must serve justice, not tradition.

Social Justice as Educational Goal

The progressive turn also redefined the meaning of justice. Traditional justice focused on individual responsibility and merit. In contrast, “social justice” emphasised collective responsibility and systemic reform. Acts of charity became obligations of justice, not personal generosity.

Jane Addams argued that individuals must “lose the sense of personal achievement” and understand their identity as part of a whole. This shift from individual to collective responsibility permeated all aspects of progressive education.

Legacy and Reflection

Pragmatism and progressivism transformed American education. They replaced rigid discipline with flexible, student-centred learning. They downplayed eternal truths in favour of evolving values. And they made education a tool for social reform.

Yet this transformation came with trade-offs. In emphasising group identity, individual autonomy often faded. In elevating change, tradition was devalued. As educators today navigate polarised demands from parents, politicians and communities, they still grapple with the legacy of progressivism: balancing innovation with continuity, social justice with personal freedom.

Reflective Prompts:

- How can educators today integrate the pragmatist emphasis on real-world outcomes without losing sight of enduring values?

- In what ways might the pursuit of social justice in education risk overshadowing individual agency and diversity of thought?

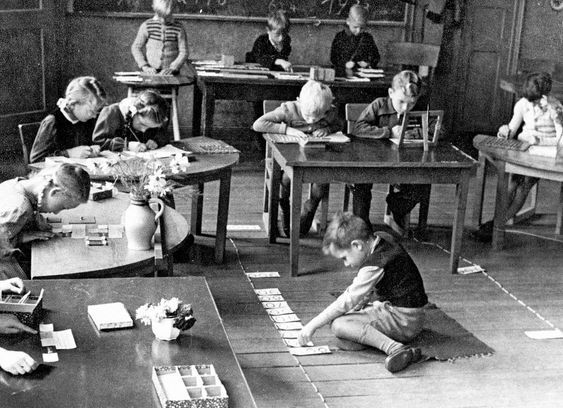

The Montessori Method

In 1907, Maria Montessori opened her first Casa dei Bambini in Rome. What began as a modest project for children deemed intellectually disabled evolved into one of the most influential educational movements of the 20th century. Montessori, a pioneering woman in medicine and engineering, developed her methods by observing neglected children and noticing their hunger not for food, but for purposeful activity and sensory stimulation.

Learning Through the Senses

Montessori’s insight was rooted in empiricism: knowledge begins with the senses. Using her training in medicine, engineering and psychology, she created “manipulatives”, which were hands-on materials designed to develop sensory perception and fine motor control. Children learned to compare sizes, match colours, button clothes and lace shoes, all through structured play. Learning was concrete, tactile and self-directed.

Each manipulative was intentionally simple, focusing attention on one concept at a time. A child playing with stacking blocks focused only on size, not colour. A dressing frame taught only zipping or buttoning. This design eliminated distractions, emphasised mastery and built confidence through trial and error, without direct instruction or correction.

The Prepared Environment

Montessori classrooms rejected the rows of desks and teacher-centred instruction typical of traditional schooling. Instead, students chose work from carefully curated materials, spread mats in open spaces and explored at their own pace. Teachers acted as guides, not lecturers: observing, encouraging and intervening only when necessary.

This approach taught autonomy and respect. Each child had ownership of their space and time, learning not only academic skills but social norms like sharing, patience and invitation-based collaboration. Multi-age classrooms allowed younger students to learn from older peers, and older students to reinforce learning by teaching.

Freedom within Structure

Montessori described her vision as “freedom in a structured environment.” Children made real choices, but always within a thoughtfully prepared setting. This mirrored her broader philosophical view: the world is governed by natural laws, yet humans flourish through agency and rationality. Education, then, should prepare the child not only to know, but to choose.

The physical and cognitive development of children was seen as a unified process. Movement and thought were interdependent. Mental development was not something separate from physical activity, it was fuelled by it.

An Individualist Ethic

Montessori education is rooted in respect for the individual child. Each learner is seen as a unique being with distinct interests and timing. Unlike collectivist or obedience-based systems, Montessori promoted self-discovery, intrinsic motivation and learner agency.

She wrote, “There exists only one real biological manifestation: the living individual; and toward single individuals, one by one observed, education must direct itself.”

Cultural Resistance and Enduring Impact

Despite its success, the Montessori model faced resistance from progressive educators like William Heard Kilpatrick, a disciple of John Dewey, who criticised its individualism and lack of emphasis on social training. Consequently, Montessori remained mostly in the private education sector throughout the 20th century.

Yet its influence on creative and entrepreneurial thinkers is hard to ignore. Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell and contemporary innovators like Jeff Bezos, Larry Page and Sergey Brin all endorsed or emerged from Montessori education. They credited it with nurturing curiosity, initiative and resilience.

Today, over 22,000 Montessori schools operate worldwide. Public school systems are increasingly experimenting with Montessori-inspired approaches, particularly as interest grows in student-centred and skills-based learning.

Education for a Changing World

Montessori’s legacy is particularly relevant in an age defined by technological disruption and entrepreneurial work. Traditional models of obedience and conformity are ill-suited to a world where adaptability, problem solving and critical thinking matter most. Montessori’s empiricist, individualist and optimistic approach may offer the best foundation for learners facing an unpredictable future.

Reflective Prompts:

- In what ways can Montessori’s emphasis on freedom within structure inform how we design learning environments today?

- How might Montessori principles be adapted for older students and adult education in a digital, fast-changing world?

Concluding thoughts…

Over time, I have come to see that the history of education is really a mirror of what we believe it means to be human. Every age has asked the same question: what kind of person should education create? Each has answered it in its own way, determined by a mixture of ideals and anxieties. The Greeks sought harmony and virtue. Kant demanded duty and discipline. Rousseau and Dewey imagined freedom through experience. Montessori trusted the quiet confidence of a curious child.

Studying these thinkers has made me look at my own learning with new eyes. I have seen how easily education can drift into routine or ideology, and how powerful it becomes when it reconnects with its moral and human purpose, determined by mixture of ideals and anxieties. Education is never just about learning for the sake of learning; it is about shaping imagination and character.

If there is one lesson I take from this long tradition, it is that education is an act of creation. It reflects who we are and shapes the kind of world we are trying to build.